The American Dissident: Literature, Democracy & Dissidence

Some for the Road: Poems for Gerald Locklin

Edited by Paul Kareem Tayyar. World Parade Books. Huntington Beach, CA. 44pp. 2008. $10.00.

Poets ought to take a moment midway through one of their numerous verse-hatching sprees to contemplate Brecht’s “Schlechte Zeit für Lyrik” (“Bad Time for Poetry”).

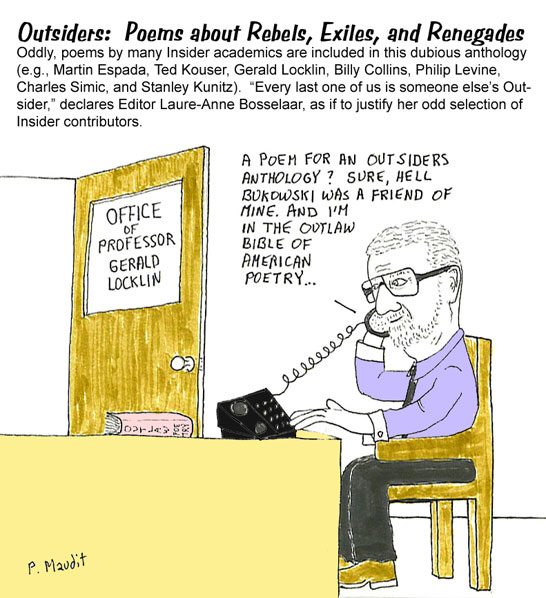

Some for the Road is an anthology of poems praising “outlaw” poet/professor Gerald Locklin, who has gained fame in the small press for, as noted in Fred Voss’ poem, “he even knew Charles Bukowski/ had gotten drunk with him/ exchanged letters with him.” Has it really gotten that bad in the milieu?

Some for the Road is an anthology of poems praising “outlaw” poet/professor Gerald Locklin, who has gained fame in the small press for, as noted in Fred Voss’ poem, “he even knew Charles Bukowski/ had gotten drunk with him/ exchanged letters with him.” Has it really gotten that bad in the milieu?

Todd Fox’s foreword reads like a speech delivered at the annual Used-Car Salesman of the Year Banquet. It’s as embarrassingly eulogizing as it gets in poetry, and that’s pretty damn embarrassing. Do we really need hagiographic volumes like this, considering the state of the world, not to mention the state of the literary established-order?

“And to make finding the words even more daunting is the fact that Gerald Locklin is a writer who needs neither our praise nor our criticism!” writes Fox. So, why the slobbering praise? “What does one say about a writer with over 200 published books, a few thousand poems in magazines too many to number…” he continues. For one thing, it says Locklin produced far too much innocuous crap like Bukowski, Lifshin, and so many other “established” poets. But even more revealing, it indicates he was not a threat to the established order. Unsurprisingly, Lifshin is one of the eulogizers in this thin volume: “…How can I write a poem/ about Bukowski and I/ and Locklin looking for a liquor store for Buk…”

Why are poets so admiring of poets who publish like beavers with pens up their asses? Rather than Fox’s two pages of vacuous tribute, it would have been interesting to read a compilation of Locklin’s own words of wisdom—are there any? “Do not be mistaken!” hails Fox. “This could easily be about Billy Collins…” Yeah, no doubt! “I mean, I write about saltshakers and knives and forks—and talk like a politician," wrote Collins.

“When does a writer know he is unimportant?” asks Fox. “The answer is easy—no one reads or talks about him.” What a simplistic assertion! So, if someone reads or talks about me, then I’m important? It doesn’t matter what I have to say? That assertion underscores just how much Fox and so many other poets so easily and willingly gravitate to the herd-yoke of adulation of the popular and famous. Who were the teachers who taught this guy? They ought to be fired on the spot. Well, it turns out that Locklin was actually one of Fox’s university professors. He was also one of Patricia Cherin’s, who writes in “An Occasional Poem for the Toad”: “I learned panegyric from you/ and encomium/ so here it is.” Perhaps the toad should have also taught the fledgling poet manicomio and suckup.

“As his successes, decade after decade, in both the academic and mainstream publishing world piled up, he continued to welcome and make room for us in his classroom and English department,” fawns Fox. It’s enough to make one vomit. What Fox needed was a professor to push him to question and challenge what being accepted really tended to mean in America. Donna Hilbert’s “Ode to the Toad,” as in “O Gerald our toad,” should have perhaps been titled “Ode to the Toadie.”

Poem after poem in this volume should not have been published, but rather sent directly to the toad god himself. To add to the inbred nature of the anthology, there’s even a syrupy poem written by son Zach, which ends thusly: “…I remember seeing the cover of Poop,/ the picture of my father naked in the bathtub,/ bearded, longhaired, spectacled,/ with a rubber ducky and an open beer can,/ and thinking,/ But Dad doesn’t drink Coors Light.” Perhaps those lines sadly sum up the reality of the average hippie recycled into tenured university professor.

Finally, these poems represent the kind of pap one would expect from poet laureates extolling the hand that feeds. They do not make one think at all. They question and challenge nothing at all. They offer no new insights or interesting thoughts. They are entirely socio-politically disengaged. If they do anything at all, they likely put a smile on Locklin’s warty face and add to the endless publication credits of the poets who wrote them. If Locklin had had any sense at all, he would have told Fox and company: no thanks. This volume epitomizes what poetry has become and is becoming in the USA today. Don’t buy it! Don’t support it!

—The Editor